As every Day

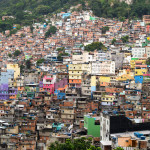

[ HIDE TEXT ][ SHOW TEXT ]In Rio de Janeiro, the self-proclaimed “Marvellous City,” one in five people live in the city’s 600 favelas; hillside communities stigmatized for drug gang violence and desperate poverty. But another side of favela life goes widely underreported: one of hope and ambition, strong community spirit and faith.

In spite of great odds – violence from drug gangs and police, racism, poverty – residents seek to improve their lot, look after their families and make the best of life. During the week people go to work and on the weekends they go out to drink and dance. On Sunday’s they might go to church. Young people look for excitement with their friends on the dance-floors and in community parties before they become bogged down – often far too early – with the responsibilities of adulthood. Teenage pregnancy often shatters the aspirations of young women while young men – usually having lacked quality education and facing pressure to be providers – are seduced by the drug gangs, with whom they can earn three times more than the local minimum wage.

At the turn of the millennium, Brazil underwent an economic boom that lifted millions out of poverty and into a new consumer class. As Brazil was awarded the World Cup and the Olympics and massive offshore oil fields were discovered off Rio de Janeiro’s coast, some dared to dream that the city was finally shaking off its reputation for violence and corruption.

Nowhere was this dream more prominent than in the favelas where violent crime dropped, real estate values soared and wages and living standards increased. But the boom faded. The big events came and went, leaving little legacy, just a hangover and a sense of wasted opportunity. Brazil’s newfound oil-fields never yielded their promised returns and investment and jobs seeped out of the city.

In the last decade, Rio’s favela residents spent big on smartphones and widescreen TVs, often on credit, but the government failed to address long-standing infrastructure problems like working sewer systems and lack of crèches.

Now, Rio de Janeiro is racked by economic and social crises. Violence in the favelas has returned and shoot-outs are now commonplace again, with stray bullets claiming ever increasing numbers of innocent victims, including many children. But life in the favela continues. Few can afford to move and many wouldn’t even if they could. For all of its problems, the community is home.

Despite recent setbacks, favela residents will continue to dream and strive. Those that can’t dream will just to try and make the best of things.